Antique cartography offers perspectives on Indigenous homelands

Last updated 5/4/2021 at Noon

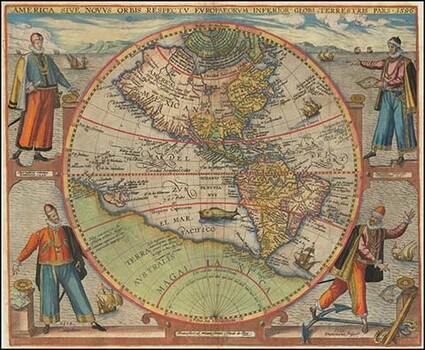

A 1596 Flemish map of the Western Hemisphere. Cartography was once more art than geography. photo provided

The Indigenous peoples of North America have been painting for millennia. They applied pigments on boulders and rock walls, on carved wooden masks and totem poles, buffalo hides and teepees.

In the latter half of the 1800s, as autonomous tribes relinquished most of their traditional ways when forced onto reservation lands, the surfaces for art were replaced by paper. Initially, important narrative imagery was applied onto closed-out accounting-ledger pages.

During the past 100 years, Native American two-dimensional artwork basically followed the same developmental paths as that of Western world art. A local Sisters art gallery hopes to shift that influence by utilizing one of the West’s more common products.

Cartography, the compilation of geographic information resulting in the mass production of maps, commenced in earnest with the printing-press revolution in the 1400s and soon began providing the masses of Europe with newfound geographic understandings during the Age of Exploration.

The early maps of the 1400s, 1500s, and 1600s showed two dimensional concepts about the placement of land, water, and national boundaries upon the Earth’s surface, but that geographic information was surrounded with and sometimes overwhelmed by artistic renderings.

Royal French Cartographer Nicolas Sanson re-envisioned maps in the mid 1600s as being straightforward geography, and the artisan era of mapping gradually fell out of favor, with Englishman John Tallis producing the last of these in the 1850s.

The early maps of the Western Hemisphere were critical to European explorers, not only for the geographic knowledge they offered, but also for providing them with a documented instrument to assert ownership over vast territories throughout the New World.

Freshly made maps, however accurate they were, along with a drawn deed and a national flag, were “legalese” tools necessary for the European nations to recognize claims on “discovered” lands, while also abrogating the oral proclamations of traditional land-ownership rights by Indigenous peoples.

The colonizing of North America notwithstanding, many of the early maps of North America depicted regional tribes occupying their homelands. Maps of the early 1800s that included tribal control of these lands offered a fascinating didactic on The United States of America, east of the Mississippi River, and Indigenous tribes west of it.

However, by 1890, the only maps still identifying the Native American people came from U.S. government offices, conveying reservation boundaries.

The owners of Raven Makes Gallery fortuitously comprehended last year that these two seemingly disparate entities — Native American artistry and antique cartography — just might be destined for each other, like chocolate and peanut butter.

Raven Makes Gallery commissioned 20 Indigenous artists from throughout North America to create works on 60 antique original maps from the 1700s and 1800s. The artistic concept is for the artists to provide perspectives on their homelands, whether in former or current times.

The larger purpose of these works does not include an effort to change what occurred. After all, the past forges an indelible history; there never can be an actual playing out of the “what if.”

The exhibition, The Homelands Collection, 1st Edition, will be held at the gallery throughout the month of May. However, no in-person artist visit will occur as has happened with previous shows at the gallery.

Raven Makes Gallery will be closed Wednesday and Thursday, May 5 and 6. It will open May 7 with the exhibition on display.

Reader Comments(0)