Supporting the fire service in wake of Sept. 11

Last updated 9/8/2021 at Noon

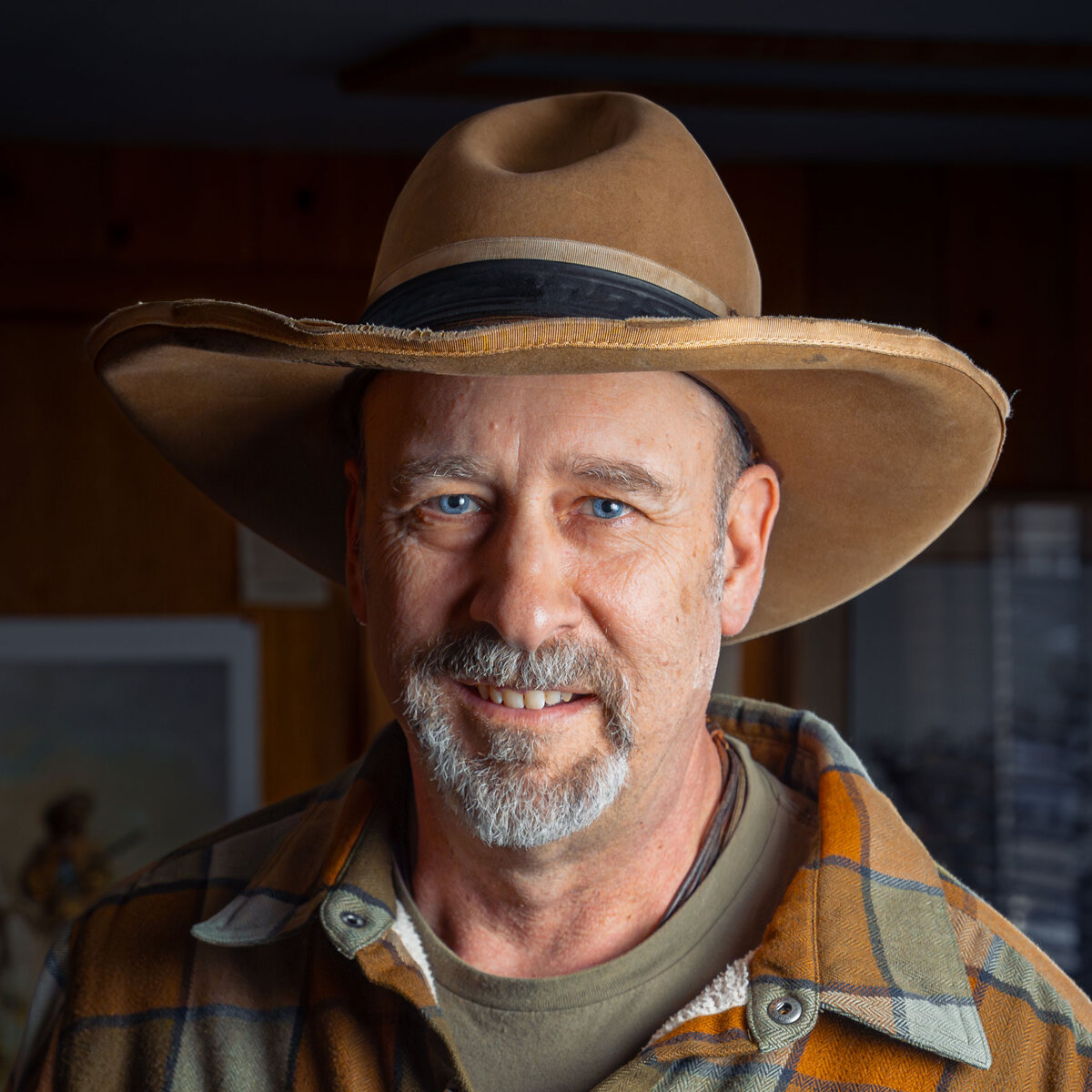

Jim Cornelius

The New York City Fire Department presented Jeff Johnson with a leather fire chief’s helmet signed by New York City public officials as a token of their appreciation for his post-9/11 work in helping to restore their department. Johnson’s crew at Tualatin Valley Fire & Rescue built a display case to house the helmet.

The September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, and the crash of a plane into a field near Shanksville, Pennsylvania, took the lives of 2,977 people — Americans and international citizens from all walks of life.

No single group took a heavier hit than the firefighters who responded to the World Trade Center. A total of 343 firefighters were killed when the towers collapsed, firefighters of all ranks, most of them from an elite cadre of highly trained rescue teams.

In the wake of the attacks, five fire chiefs from across America were tapped to help the devastated New York City Fire Department (FDNY) recover from its losses. Among them was Jeff Johnson, who is now CEO of the Western Fire Chiefs Association and principal of Sisters Meat & Smokehouse.

In 2001, Johnson was chief of Tualatin Valley Fire & Rescue.

“I was driving in to work and listening to the radio when it happened,” he recalled. “I called [wife] Kay and said, ‘Get the kids up and turn on the TV.’”

He suspected “bad actors,” and the second plane hitting the second tower of the World Trade Center confirmed it. America was under attack — and Johnson had work to do.

Even in a fire district remote from New York City, the immediate response was to prepare.

“We didn’t know how extensive this was going to be,” Johnson said.

Even if there were no follow-on attacks elsewhere in the nation, Johnson knew that departments like his were going to be affected. Many of his personnel were serving in the National Guard and would likely be called up as part of a national response, which would mean changes for his crew.

“No matter what, we had work to do and needed to get going,” Johnson recalled.

The chief and his firefighters were well aware that their brothers in the service were in mortal danger from the attacks. The planes that impacted the towers had exploded, and intense fires were burning. The world watched as smoke billowed from the towers into the blue New York sky.

“I knew when the first building came down that there were a lot of firefighters in there,” Johnson said. “Because, where else would they be?”

Johnson well understood what the firefighters in New York were facing.

Command decisions were acutely fraught, and the logistics of a rescue effort daunting.

“Do you keep your people out or do you send them in?” Johnson said.

As fire chiefs set up command posts, bodies began falling from the sky as people jumped to their death to escape the flames and smoke engulfing the top floors of the towers. With 911 operators telling frantic callers in the towers to stay in place and await rescue, firefighters simply had to go in. And they had to climb, because elevators were either inoperable or unsafe to use.

“You knew it was going to be harder than it seemed,” Johnson said. “Just think of the fitness required for those guys.”

Johnson was not in the least surprised that hundreds of firefighters shouldered the load and climbed straight up into mortal danger.

“When you’re faced with that moment, there’s not a lot of contemplation or philosophy and theology of what you’re doing,” he said. “You’re not going toward that building and turning your back on the four guys you’ve worked with your whole career. Your attitude is, you win together and you lose together, and whatever happens, happens to all of us.”

What happened was as bad as it gets. The towers collapsed, with hundreds of firefighters inside still trying to get to trapped people and get them down the stairs and out.

“The pancake collapse made perfect sense,” Johnson said. “We’re trained to understand that.”

It took days to tally the toll, and weeks and months to come to terms with it.

In late October, Johnson received a call from the U.S. Fire Administration asking him to travel to New York City as part of a team helping the fire department address the strategic considerations that had developed in the wake of a devastating loss of personnel. Recovery teams were still finding bodies of firefighters in the rubble of Ground Zero, and the department was in the midst of months of funerals and memorials.

Tom Von Essen was FDNY Commissioner of the City of New York on September 11, 2001. He and Johnson remain friends. Von Essen told The Nugget that the help from Johnson and his colleagues was deeply appreciated.

“They were so valuable to us, because most of our guys were just an emotional wreck at the time,” he said. “All they wanted to do was go to the site and dig.”

From a strategic perspective, the challenge the department faced was not simply replacing lost personnel.

“Replacing the experience we lost was the hard part,” Von Essen said.

Johnson noted that most of the firefighters who perished were “the special forces, those were the rescue teams.” Command personnel who came up through the ranks and were lost carried a unique depth of experience.

According to Von Essen, the years 1965-75 were the busiest in the history of the FDNY.

“Anybody who was around at that time had an enormous amount of experience nobody will ever have again,” he said.

Johnson’s team was tasked with helping to come up with a plan to get personnel recruited and trained and out on the street quickly. Many firefighters were promoted into higher ranks and greater responsibility.

Promotion is usually a celebratory time in the fire service, but Von Essen recalled that this one was wrenching.

“It was not a happy time; there was no way to make it a happy time,” he said. “That promotion ceremony was a nightmare, looking back on it.”

Von Essen was awash in a sea of grief. He was fully engaged with the operational work of getting his department back into shape, which he described as a challenge that was “everything a leader wants to do.”

But that work was overshadowed by his duty to preside over dozens of funerals and memorials. He was the right man for the job, because he loved his people and knew the job inside out — but it was very tough duty.

“The grief was something I wouldn’t wish on anybody,” he said. “It really was the hardest thing I’ve done in my life.”

Johnson recalled seeing massive impromptu memorials created by New Yorkers in front of every fire station. He noted that the fire service is “a family business,” and some families had lost multiple members on September 11. The wreckage of fire apparatus was stark testament to the maelstrom that had taken those lives.

“There were holes in the sides of fire trucks that you could put your head in,” Johnson said.

Communications had been disastrously flawed on September 11, 2001, and Johnson would go on to work for years with legislators to fulfill a 9/11 Commission recommendation that first-responder public safety communications be overhauled.

“Now public safety has its own broadband network,” he said. “That’s what you now know as FirstNet.”

The legacy of 9/11 includes a much deeper appreciation for the “service over self” ethic of fire fighters.

“People treated firefighters differently after 9/11,” Johnson said.

He sees firefighters as “ordinary people with a very strong sense of mission and an unbelievable level of loyalty.”

In a public speaking career that takes him around the world, Johnson says he often reminds audiences of what the 343 firefighters who died on September 11, 2001, represent.

“I remind them of the sacrifice of those 343 and how every single one of us in one way or another has been a beneficiary of their sacrifice.”

Reader Comments(0)